Ukraine has just a few weeks left before a two-year moratorium on $20 billion of bonds ends and it has to resume interest payments to private creditors. Talks about a restructuring have so far failed to yield a deal, with the parties at loggerheads over how much of their investment bondholders should sacrifice.

With Russia’s full-scale invasion now in its third year, Ukraine wants to lower its debt payments to save limited resources for the battlefield and to keep government services functioning. At the same time, Kyiv needs to maintain good relations with creditors for the reconstruction of its economy once the fighting eventually ends.

- How stretched are Ukraine’s finances?

Ukraine spends almost all of its domestic revenue to finance the war, with fiscal assistance from the European Union, the US and the International Monetary Fund used to cover social services.

A $61 billion aid package that US lawmakers approved in April has earmarked $7.8 billion for budget support, while the remaining portion includes military assistance in the form of weapons. Ukrainian Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko has said the aid will help to cover his budget for this year, but that the outlook for 2025 remains uncertain, with a possible “additional” deficit of as much as $12 billion if the war continues at its current pace.

What complicates matters is that any forecast of Ukraine’s financial capacity remains subject to how the war evolves. Currently, there’s no end in sight to the fighting, and Russia has stepped up attacks on critical infrastructure. As it stands, the government expects that the economy will expand by 3.5% this year, down from an earlier forecast of 4.6%. Gross domestic product is still a quarter below the level it was when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022.

- What do bondholders want?

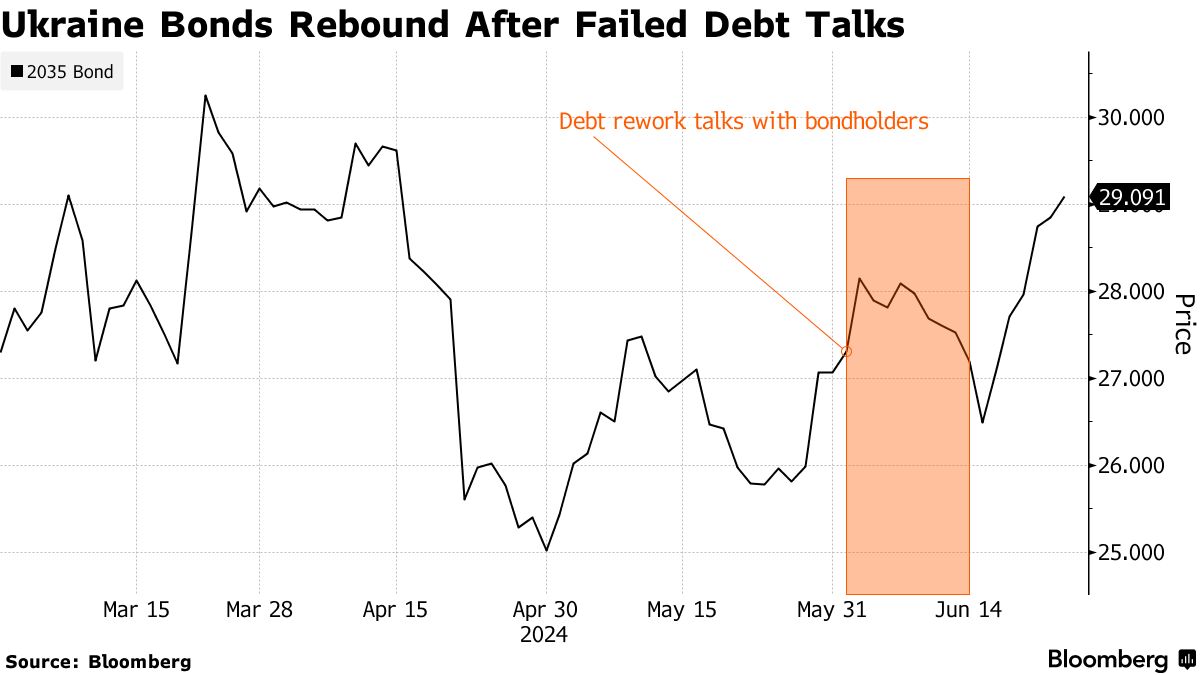

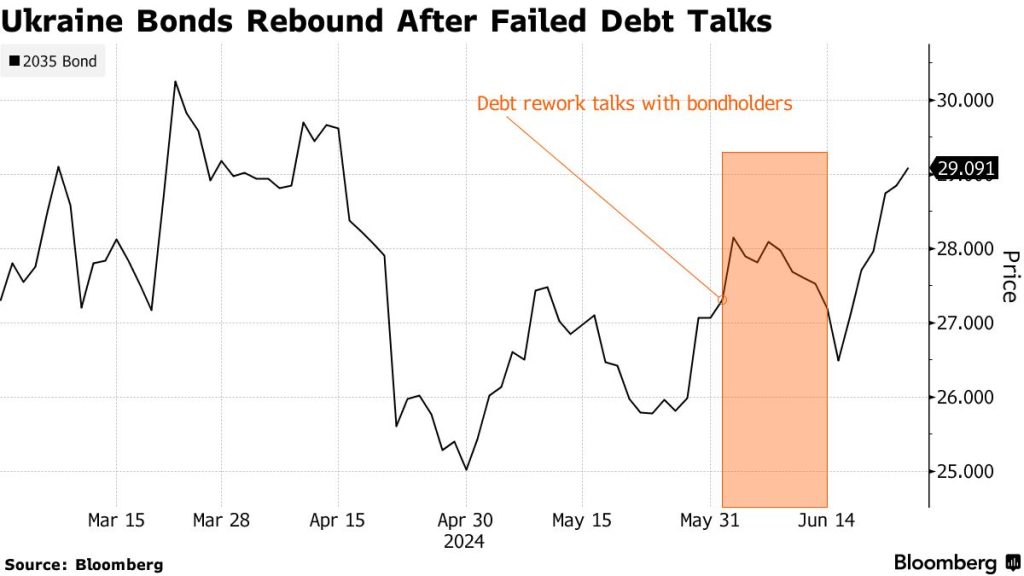

In talks with private lenders that ended without a deal on June 14, creditors were unsatisfied with the level of debt cancellation that Ukraine proposed. The government was pressing for a haircut of as much 60 cents out of every dollar owed, while bondholders were only ready to shoulder losses of 22.5%.

Ukraine was looking to push back its payment obligations, proposing to exchange its outstanding bonds for new debt with maturities running as late as 2040 and interest payments starting at 1% for the first 18 months, before progressively increasing to 6%.

The government also offered investors a so-called state contingency instrument that could begin payments only after 2027. Payments on that instrument would be related to tax revenue targets set by the IMF.

- What is the role of the IMF?

The IMF is key to any deal as the lender’s $15.6 billion loan to the country — awarded in March 2023 and a first for a nation at war — sets metrics for what it deems to be affordable debt payments. Ukraine’s latest proposals fit those metrics, according to the government. An updated picture of the IMF’s economic growth and debt estimates will emerge after its executive board signs off on a $2.2 billion tranche of its program, expected on June 28.

- What happens if the debt talks fail to secure a deal?

Ukraine wants to keep good relations with private investors and, with the payment-standstill expiring soon, the two sides will have to either restructure the debt or continue the pause to avoid a sovereign default. Analysts at JPMorgan Chase & Co. have suggested that an extension of the moratorium could be possible, likely for a few months rather than another two years.