In the first two months of 2025, Uzbekistan’s natural gas production declined by 4.2% compared to the same period in 2024, continuing a troubling trend that has seen output fall from 61.59 billion cubic meters in 2018 to 44.59 billion cubic meters in 2024. This persistent decrease raises concerns about the nation’s energy security and economic stability.

Once among Central Asia’s energy success stories, Uzbekistan became a net importer of natural gas in 2023, a symbolic turning point for a country whose identity was long intertwined with hydrocarbon abundance.

The extent of the strain was demonstrated in December 2024, when gas stations around the country were forced to close during a cold snap as heating systems across the country kicked into action. This led drivers of methane-powered cars, which are common in the country given that it costs about $15 to fill the tank as opposed to $40-50 in a gasoline-powered vehicle, into a desperate hunt for places to fill up. Kilometer-long queues formed, and drivers ferociously competed to be first to the pump.

Such scenes have become a familiar sight in the Uzbek winter as gas production has fallen.

“Uzbekistan’s gas production is already quite mature,” Anne-Sophie Corbeau of Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy told The Times of Central Asia. “The existing fields are entering a phase of decline. The reserve-to-production ratio was around 18 years based on 2020 data, and the situation is unlikely to be much better now.”

Put simply, the country is running out of easy gas. Despite repeated efforts to locate new reserves, particularly in the under-explored Ustyurt region, exploration has so far failed to yield significant breakthroughs. Even if discoveries are made, the timeline to bring new fields online would mean little impact before 2030, at best.

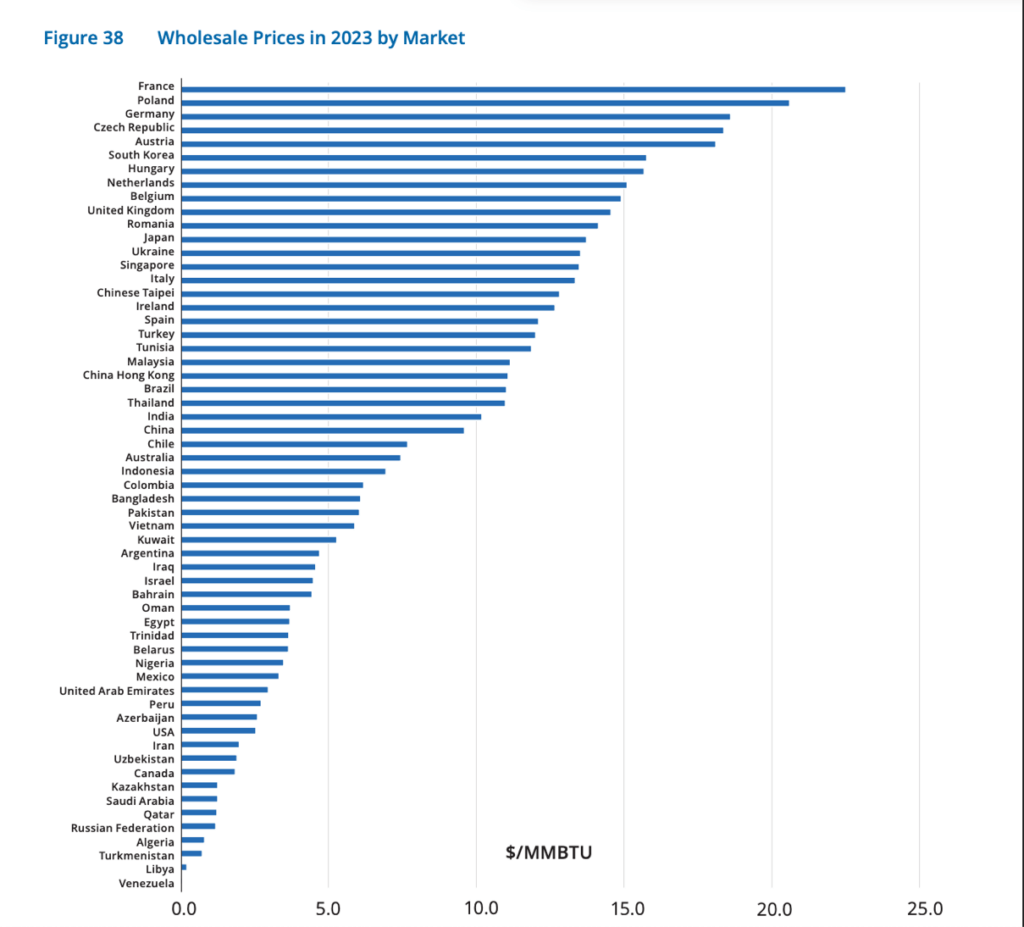

In parallel, demand for gas has remained stubbornly high. Corbeau noted that “the country’s energy mix and electricity generation are very dependent on natural gas. And Uzbekistan is one of the countries with the lowest wholesale gas prices in the world.” Those prices have long distorted both domestic consumption and investor interest, keeping demand high while choking off potential upstream capital.

This sentiment is echoed by Irina Mironova, Senior Energy Analyst at the New Energy Advancement Hub. “Domestic production is declining faster than consumption,” she said, “and domestic gas pricing is not market-based. It remains below the price of imported gas, which undermines the investment appeal of upstream projects for foreign investors.”

The government has undertaken some measures to control demand over the past year, raising the tariffs for electricity and gas by 52.5% and 71% respectively, hitting consumers in the pocket in an attempt to alter the wasteful use of scant resources.

On the supply side, the government has declared a bold ambition to raise production to 62 billion cubic meters annually under its Uzbekistan–2030 development strategy, but observers remain skeptical. “They’ve tried to facilitate exploration, especially in the Ustyurt region,” says Corbeau. “But even if results are positive, it’s unclear if significant production can be up and running by 2030.”

In 2019, Uzbek state television announced that British oil major BP and Azerbaijan’s state oil company SOCAR would lead exploration into the potential of gas reserves in the Ustyurt Plateau in the far west of the country. BP abandoned the project in 2021, with Tashkent blaming the company’s new focus on low-carbon projects. SOCAR retained an interested and signed a strategic partnership with Uzbekneftegaz in 2024, but six years on from BP’s initial interest, the two companies are still at the “initial exploration” stage, suggesting BP’s concerns may have been more than simply environmental.

Return of the Mack

Right now, Uzbekistan is looking to imports to bridge the gap. The timing is auspicious: Russia’s Gazprom, once focused almost entirely on Europe, has redirected its gaze to Central Asia in the wake of Western sanctions and lost market share. In November 2022, Moscow proposed a “gas union” with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, offering Russian supply to compensate for the region’s faltering output.

The Soviet era Central Asia–Center pipeline, once used to transport gas from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Russia, has now been engineered to run in reverse. Exports to Uzbekistan in the year to October 2024 exceeded five billion cubic meters.

But are these offers strategic, even predatory?

Not quite, says Corbeau. “Russia stepped in because both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan each had pipeline export commitments to China – 10 bcm per year each – that they failed to deliver.” She explained that Russia saw an opportunity to fill that gap, sending gas to these two countries, who could then continue to export their own gas on to China. For Russia, it was “a good way to reach China, without building additional infrastructure.”

Mironova agrees that Russia’s motives are largely economic, not geostrategic. “Gazprom is likely to maximize the sales price under current market conditions. Given that Uzbekistan has some level of domestic production, it offers opportunities to integrate local output and optimize costs. If there were a viable opportunity for production expansion, I believe Gazprom would seek involvement rather than attempt to undercut local production.”

That said, Gazprom’s own challenges make it an unreliable savior. The company’s finances have been battered by the collapse in European sales. As Mironova noted, “Following the reduction of gas exports to Europe in 2022 – and especially given Gazprom’s financial difficulties in 2024 – the company’s investment capabilities have been significantly reduced. Uzbekistan is unlikely to be a priority.”

Other sources

In the long run, Tashkent is seeking to diversify. In December, the government announced that twelve modern thermal power plants will be installed by 2027, with almost $5 billion of investment in public private partnerships with companies from France, Germany and Japan. Meanwhile, Russia’s Rosatom has begun work on a small-scale nuclear power plant near the picturesque Tuzkan Lake.

“Uzbekistan aims to derive 54% of its electricity from renewables by 2030,” said Mironova. While current capacity is measly – wind and solar comprised less than 1% of its energy needs in 2023 – the country has made some recent steps forward. The country is currently constructing a series of renewable energy projects worth around $13 billion.

Posters across Tashkent have declared “2025 is the Year of Environmental Protection and the Green Economy”, echoing Mirziyoyev’s announcement in January. Two major wind energy projects in the Bukhara region, built by Chinese and Saudi investors, should have come online by 2026.

Meanwhile, in a country which averages 320 sunny days per year, solar has huge potential. A top-down order in January from Energy Minister Jurabek Mirzamakhmudov stipulated that 50% of all roofs in the nation will have solar panels installed on them, although specific details were lacking.

Electric cars are now increasingly populating the streets of Tashkent, with the Chinese firm BYD opening its first factory outside China in Mirziyoyev’s hometown of Jizzakh.

At the recent EU-Central Asia summit in Samarkand, the European Union made climate and energy one of its four key pillars of cooperation with Central Asia. Given Tashkent’s recent push toward regional leadership and Central Asia’s more general push toward economic integration, it also stands to benefit from hydroelectric projects in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Still, the road to an energy-secure Uzbekistan is bumpy and potholed. Grid infrastructure remains underdeveloped, and familiar allegations of corruption in procurement remain a concern. With the country’s economy and population both booming, demand will continue to surge. As a result, natural gas will likely remain a cornerstone of the energy mix for years to come, leaving the country in a race against time to develop alternatives.